Why are alcoholic beverages called “spirits”? Because when you drink them strange “spirits” rise within your mind and body. That’s all that “spirits” are: intangible feelings we don’t fully understand and the emotional experiences that go along with them. Understood in this way, “spirituality” is just another way of saying “emotionality” — or learning to understand and interact with one’s strong emotions.—Dave Swindle at PJMedia.

Thus, the danger of “spiritual but not religious” is that a practitioner engages with spirits (strong emotions and religious rituals) without having any guidance for how to interpret them.

Someone who is “spiritual but not religious” doesn’t know if the spirit they’re invoking is an “angel” (symbol of God, our higher nature) or a “demon” (symbol of death, our animal nature) because they don’t have a religious foundation to guide them upward. They’ve ignored the collective wisdom of humanity and decided to just set their own course. They’ve made themselves their own god. And they reap the consequences: unhappiness.

Showing posts with label faith. Show all posts

Showing posts with label faith. Show all posts

Monday, August 13, 2012

Spiritual, but not religious

Tuesday, January 24, 2012

Why I Chose God

For me, the essence of "faith" is choice, and the key quality is "nevertheless." Faith is the very tension between yes and no, between reliance and rejection, and is the occasion for making an utterly personal decision all by yourself, all for yourself.

It works like this:

On the one hand, I really, honestly, do see, hear, and experience everything that atheists adduce as evidence that God is an illusion. What is more, as a former executive in a brain-monitoring company I understand perhaps better than most of them the scientific basis for their argument that there is no "there" there beyond some intracranial synapses creating an illusion some call "God".

On the other hand, I also see, hear, and experience in my everyday life what I just as really, honestly, understand as God.

This brings me to a free choice: I can choose to live my life according to either one depiction or the other: without God or with God. The act of "faith" is choosing one over the other "nevertheless." The nevertheless means I don't deny, dispute, or dishonor the evidence and the argument to the contrary; it simply means that I choose not to adopt it as the definitive guide for my own thinking and feeling and actions during what poet Mary Oliver calls my "one wild and precious life." Perhaps the same process holds true for those atheists who acknowledge that there really are two sides to this issue: they, too, see some evidence on both sides, weigh it, and choose the alternative instead (although I can imagine that calling this decision an act of "faith" might not be very palatable to some).

Eliot Daley, quoted in the Huffington Post.

Monday, July 25, 2011

Why Tolerance is Condescending

Penn Jillette is a very talented magician, the more statuesque half of Penn and Teller. He is also an outspoken atheist. Yet he remains one of the, if not nicest, then honest, ones and often has good things to say about sincere believers, even if he believes them sincerely wrong. Here's an example:

"One of the reasons I get along so much better with fundamentalist Christians than I do with liberal Christians, is that fundamentalist Christians, I can look them in the eye and say, 'You are wrong.' They also know that I will always fight for their right to say that. And I will celebrate their right to say that. But I will look them in the eye and say, "You're wrong." And the fundamentalist will look me in the eye and say, 'You're wrong.' And that, to me, is respect.

"The more liberal religious people who go, 'There are many paths to truth, you just go on, and maybe you'll find your way' --[this] is the way you talk to a child, and I bristle at that."Here is the video which includes the comment. Warning: Not all of it is as polite.

Saturday, June 4, 2011

Christopher Hitchens embraces faith?

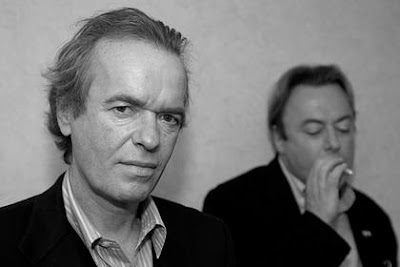

|

| Martin Amis and Christopher Hitchens |

Christopher Hitchens, my favorite athiest, is dying of esophageal cancer. Numerous pleas for him to embrace faith have been met with just as many pledges never to do so. But from novelist Martin Amis, whom Hitchens calls his "dearest friend," comes perhaps the most interesting entreaty of all:

My dear Hitch: there has been much wild talk, among the believers, about your impending embrace of the sacred and the supernatural. This is of course insane. But I still hope to convert you, by sheer force of zealotry, to my own persuasion: agnosticism. In your seminal book, God Is Not Great, you put very little distance between the agnostic and the atheist; and what divides you and me (to quote Nabokov yet again) is a rut that any frog could straddle. "The measure of an education," you write elsewhere, "is that you acquire some idea of the extent of your ignorance." And that's all that "agnosticism" really means: it is an acknowledgment of ignorance. Such a fractional shift (and I know you won't make it) would seem to me consonant with your character – with your acceptance of inconsistencies and contradictions, with your intellectual romanticism, and with your love of life, which I have come to regard as superior to my own.

The atheistic position merits an adjective that no one would dream of applying to you: it is lenten. And agnosticism, I respectfully suggest, is a slightly more logical and decorous response to our situation – to the indecipherable grandeur of what is now being (hesitantly) called the multiverse. The science of cosmology is an awesome construct, while remaining embarrassingly incomplete and approximate; and over the last 30 years it has garnered little but a series of humiliations. So when I hear a man declare himself to be an atheist, I sometimes think of the enterprising termite who, while continuing to go about his tasks, declares himself to be an individualist. It cannot be altogether frivolous or wishful to talk of a "higher intelligence" – because the cosmos is itself a higher intelligence, in the simple sense that we do not and cannot understand it.After reading that, I felt compelled to say that Amis is right: The only logical and reasonable stance concerning God (that is, solely based on logic and reason) is that of agnostic. I readily admit my faith and belief in God is exactly that: faith and belief. Yet Hitchens probably does not admit that his denial of the existence of God is equally a stand of faith and belief, and not logic and reason.

So, I guess you could say Christopher Hitchens has embraced faith. Of a sort.

—Wayne S. (Martin Amis quote From "Amis on Hitchens" in The Guardian.)

UPDATE: The above quotation also appears in Amis's foreword to The Quotable Hitchens.

UPDATE: The above quotation also appears in Amis's foreword to The Quotable Hitchens.

Monday, April 4, 2011

Repost: Love Like God, or Love of God?

Since the current debate in Christian circles centers around the love of God, I thought a couple of you might find this entry, from 2009, of renewed interest.

Perhaps the most quoted New Testament writer of all is not Paul, but the Apostle John. There are two reasons for this: John 3:16 and First John 4:8.

"For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish, but have eternal life." John 3:16

"The one who does not love does not know God, for God is love." 1 John 4:8

The former verse is, of course, a great promise to believers and unbelievers alike. The latter is a promise, too, that we will know the true spiritual state of our hearts by our actions towards others.

Unfortunately, many (mostly those outside the faith) want to make the second verse mean something it does not. They want it to mean that "If we love, we know God." But it doesn't. If we love, we are perhaps most like God, but we do not neccessarily know Him. I may sit down and play "Yesterday" on the guitar, but I do not know Paul McCartney.

John speaks about love a lot. Severty-nine times it is used in his writings. It is obvious that he thinks love is a paramount virtue, and evidence of a true spiritual faith. One would think the writer John would be a perfect text for those who say "the essence of spirituality is love."

But John also says something else. In the same letter in which he wrote "God is love," he writes this:

"By this you know the Spirit of God: every spirit that confesses that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God; and every spirit that does not confess Jesus is not from God; this is the spirit of the antichrist*, of which you have heard that it is coming, and now is already in the world." 1 John 4: 2-3

Yikes! Suddenly we find that loving one another is not enough. We actually need to confess that Jesus is God, sent from God. Here's where the "God is love" crowd drops back. But in doing so, don't they really negate the love part, too? I mean, if John is dead-set on this Jesus stuff, can we trust him on the love stuff?

Many Americans, Christian or not, simply choose to ignore the Jesus stuff. A Pew Research Center survey in 2007 found that in all major religions (including evangelical Christianity), a majority felt there were many roads to eternal life. Even our president unashamedly supports this view. But John doesn't. And neither does the rest of the Bible.

John sums it up this way:

Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God; and everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. The one who does not love does not know God, for God is love.By this the love of God was manifested in us, that God has sent His only begotten Son into the world so that we might live through Him. In this is love, not that we loved God, but that He loved us and sent His Son to be the propitiation for our sins.Beloved, if God so loved us, we also ought to love one another.No one has seen God at any time; if we love one another, God abides in us, and His love is perfected in us. By this we know that we abide in Him and He in us, because He has given us of His Spirit.We have seen and testify that the Father has sent the Son to be the Savior of the world. Whoever confesses that Jesus is the Son of God, God abides in him, and he in God.We have come to know and have believed the love which God has for us. God is love, and the one who abides in love abides in God, and God abides in him.By this, love is perfected with us, so that we may have confidence in the day of judgment; because as He is, so also are we in this world.There is no fear in love; but perfect love casts out fear, because fear involves punishment, and the one who fears is not perfected in love.We love, because He first loved us. (1 John 4:7-19)

Yes, God is love. And Jesus is the evidence. The only evidence.

—W. S.

*John uses the term antichrist here in a generic sense, as someone who is anti-Christ, not as some prophetic future ruler.

Illustration: Helping Hands by Nadeem Chughtai

Saturday, August 7, 2010

Can a person without faith be healed?

This question came up in a weekly reading group I attend. (I call it that, although the only book we read is the Bible. But that's all we do—read a chapter and then comment on it. Sounds like a recipe for disaster, but although we have a diverse group of young and old Christians, Orthodox and Messianic Jews, and the occasional seeker or unbeliever, the comments are uniformly rich, encouraging and challenging. Must be God or something.)

The general consensus was that yes, a person without faith can be healed. Among the reasons cited:

But I will be praying for him. He sees it as late in his story. But perhaps it is finally just beginning.

The general consensus was that yes, a person without faith can be healed. Among the reasons cited:

The same question was revived in real-time this week when Christopher Hitchens, my favorite atheist, was interviewed by Jeffrey Goldberg of the Atlantic. Hitchens, the author of God Is Not Great, was recently diagnosed with esophageal cancer. When Goldberg asked him if he were insulted by people praying for him, Hitchens, in typical wry humor, replied:

- God is God. He can do whatever he pleases. He is not a God of formula.

- Often it is only the faith of others, not the ill person, which precedes healing.

- People have been healed who were comatose or dead. (See Luke 8)

"No, no, I take it kindly, on the assumption that they are praying for my recovery."Hitchens makes it clear that such a result will not sway his unbelief. If gratitude were a requirement for healing, Hitchens might have a point. Yet in Luke 17, when ten lepers were healed, only one came back to say thanks. And we know that, every day, hundreds of things come into our lives which should make us grateful, but we fail to even see them.

But I will be praying for him. He sees it as late in his story. But perhaps it is finally just beginning.

Sunday, June 6, 2010

Remembering Normandy, June 6, 1944

Remembering the many, many men who fell in battle on this day 66 years ago. Here is a video which shows one way that remembrance was shown. The videographer explains:

While visiting the American cemetery in Normandy, a French gentleman and his friends came upon Amos, and when he realized that Amos was a WW2 veteran who fought in Normandy, the French gentleman gave Amos a letter.

Sunday, May 9, 2010

The Color of Water

The Color of Water by James McBride. A book review.

In one sense, it is a remarkable story about a mother who married two good men and raised twelve children, among them medical doctors, university professors, journalists and musicians. In another, it is a story of faith, as Ruth McBride goes on, with her husband, to co-found a Baptist church in New York. Yet it is made all the more noteworthy because Ruth was a white, Jewish woman, and both her husbands were black. In the ultimate sense, therefore, the most redemptive part of this story may be how God raised her above prejudice—Jew against gentile, white against black, black against white, even dark-skinned blacks versus light-skinned—and gave her, her twelve children, and her grandchildren a wonderful gift.

Ruchel Dwara Zylska, the daughter of a failed itinerant Orthodox rabbi, fled her native Poland with her family in 1921 and settled in Suffolk, Virginia. Her father was a cruel man who abused his crippled wife and mistreated his daughter. Along with this harsh treatment, she and her family were ostracized in the South because they were not white, but “Jews.”

Working long hours in her father’s mercantile store in a black community, she began to identify with the black children her age, also marginalized and discriminated against. Ruth Shilsky (her Americanized name) fled persecution once again when, at seventeen, she moved to New York. There she met Andrew Dennis McBride, a violinist from North Carolina studying music. He was a deacon and choir member at a Harlem church, where she began attending, and where something else happened:

The author, James McBride, tells his own story beside hers. Her vivid recollections, dictated reluctantly at first, match perfectly James’s story of growing up with “the strange, middle-aged white lady riding her ancient bicycle.” In places the story is hard (both of Ruth’s husbands die, leaving her with eight and then twelve children to raise; James faces the hurdles of inner-city gangs and drugs), and finding their way was hard for both James and Ruth. Yet it is a powerful story of God’s grace. James became

a jazz musician, journalist and author, and Ruth earned a B.A. in Social Work at age 65.

The evocative title comes from a conversation between mother and son:

In one sense, it is a remarkable story about a mother who married two good men and raised twelve children, among them medical doctors, university professors, journalists and musicians. In another, it is a story of faith, as Ruth McBride goes on, with her husband, to co-found a Baptist church in New York. Yet it is made all the more noteworthy because Ruth was a white, Jewish woman, and both her husbands were black. In the ultimate sense, therefore, the most redemptive part of this story may be how God raised her above prejudice—Jew against gentile, white against black, black against white, even dark-skinned blacks versus light-skinned—and gave her, her twelve children, and her grandchildren a wonderful gift.

Ruchel Dwara Zylska, the daughter of a failed itinerant Orthodox rabbi, fled her native Poland with her family in 1921 and settled in Suffolk, Virginia. Her father was a cruel man who abused his crippled wife and mistreated his daughter. Along with this harsh treatment, she and her family were ostracized in the South because they were not white, but “Jews.”

Working long hours in her father’s mercantile store in a black community, she began to identify with the black children her age, also marginalized and discriminated against. Ruth Shilsky (her Americanized name) fled persecution once again when, at seventeen, she moved to New York. There she met Andrew Dennis McBride, a violinist from North Carolina studying music. He was a deacon and choir member at a Harlem church, where she began attending, and where something else happened:

In 1942, Ruth said to Andrew Dennis McBride, “I want to accept Jesus Christ into my life and join the church.”When it became apparent that Ruth intended to marry Dennis, her Jewish family sat shiva for her, proclaiming her dead to them. From that moment on, her community was the black community of her husband and her soon-to-follow children.

Dennis said, “Are you sure you want to do this, Ruth? You know what this means?”

I told him, “I’m sure.” I was totally sure.

The author, James McBride, tells his own story beside hers. Her vivid recollections, dictated reluctantly at first, match perfectly James’s story of growing up with “the strange, middle-aged white lady riding her ancient bicycle.” In places the story is hard (both of Ruth’s husbands die, leaving her with eight and then twelve children to raise; James faces the hurdles of inner-city gangs and drugs), and finding their way was hard for both James and Ruth. Yet it is a powerful story of God’s grace. James became

a jazz musician, journalist and author, and Ruth earned a B.A. in Social Work at age 65.

The evocative title comes from a conversation between mother and son:

[O]ne afternoon, on the way home from church, I asked her if God was black or white.—Wayne Steadham

A deep sigh, “Oh boy…God’s not black. He’s not white. He’s a spirit.”

“Does he like black or white people better?”

“He loves all people. He’s a spirit.”

“What’s a spirit?”

“A spirit’s a spirit.”

“What color is God’s spirit?”

Sunday, March 7, 2010

Love, forgiveness and grace

Photo: Fox News

"I converted to Christianity because I was convinced by Jesus Christ as a character, as a personality. I loved him, his wisdom, his love, his unconditional love. I didn't leave [the Islamic] religion to put myself in another box of religion. At the same time it's a beautiful thing to see my God exist in my life and see the change in my life. I see that when he does exist in other Middle Easterners there will be a change.

"I'm not trying to convert the entire nation of Israel and the entire nation of Palestine to Christianity. But at least if you can educate them about the ideology of love, the ideology of forgiveness, the ideology of grace. Those principles are great regardless, but we can't deny they came from Christianity as well."

—Mossab Hassan Yousef, son of Hamas founder Sheikh Hassan Yousef, from an interview in the Wall Street Journal. He is the author of the new book Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable Choices .

.

Saturday, February 6, 2010

My favorite atheist

In a recent interview with a Unitarian Minister, Marilyn Sewell, Hitchens makes some amazing, and true, comments about Christianity:

SEWELL: The religion you cite in your book is generally the fundamentalist faith of various kinds. I’m a liberal Christian, and I don’t take the stories from the scripture literally. I don’t believe in the doctrine of atonement (that Jesus died for our sins, for example). Do you make and distinction between fundamentalist faith and liberal religion?

HITCHENS: I would say that if you don’t believe that Jesus of Nazareth was the Christ and Messiah, and that he rose again from the dead and by his sacrifice our sins are forgiven, you’re really not in any meaningful sense a Christian.

SEWELL: Let me go someplace else. When I was in seminary I was particularly drawn to the work of theologian Paul Tillich. He shocked people by describing the traditional God—as you might as a matter of fact—as, “an invincible tyrant.” For Tillich, God is “the ground of being.” It’s his response to, say, Freud’s belief that religion is mere wish fulfillment and comes from the humans’ fear of death. What do you think of Tillich’s concept of God?”I certainly enjoyed that. Didn't you? Of course, if a Christian said "you're really not in any meaningful sense a Christian," they would be accused of self-righteousness and being judgmental. But when one who has no affinity says it, perhaps it carries more weight.

HITCHENS: I would classify that under the heading of “statements that have no meaning—at all.” Christianity, remember, is really founded by St. Paul, not by Jesus. Paul says, very clearly, that if it is not true that Jesus Christ rose from the dead, then we the Christians are of all people the most unhappy. If none of that’s true, and you seem to say it isn’t, I have no quarrel with you. You’re not going to come to my door trying convince me either. Nor are you trying to get a tax break from the government. Nor are you trying to have it taught to my children in school. If all Christians were like you I wouldn’t have to write the book.

Read the entire interview here.

Sunday, January 24, 2010

God or gods?

In reality there are as many religions as there are individuals. —Mohandas Gandhi, in Gandhi: 'Hind Swaraj' and Other Writings Centenary Edition (Cambridge Texts in Modern Politics)

There are more idols in the world than there are realities. Friedrich Nietzsche, in Twilight of the Idols

While it lasts, the religion of worshipping one's self is the best. — C. S. Lewis, in God in the Dock

I think God is all things. So, you're God. This table is God. My children, the flower. For heaven's sakes, that flower's God. The sound of that saw, that's God. See, I went from religion to then studying physics and string theory and those things. You study, you get into string theory and all that, quarks and the time continuum. And you really start realizing God. -- Melissa Ethridge, in The God Factor.

I think God is all things. So, you're God. This table is God. My children, the flower. For heaven's sakes, that flower's God. The sound of that saw, that's God. See, I went from religion to then studying physics and string theory and those things. You study, you get into string theory and all that, quarks and the time continuum. And you really start realizing God. -- Melissa Ethridge, in The God Factor.

These four, from very different perspectives, seem to all be saying the same thing: It is easiest to have a god who is most like you, or perhaps even you. We want a god who makes us feel right, who justifies our goodness.

In the 21st century, we may laugh or scoff at the ancient religions (and several current ones) who had a god for everything--sex, food, war; the list is endless. Yet do we not sometimes do the very same thing?

The premier moral code for modern society is the Decalogue--the Old Testament Ten Commandments. It is no accident the first one reads:

You shall have no other gods before Me. You shall not make for yourself an idol, or any likeness of what is in heaven above or on the earth beneath, or in the water under the earth. You shall not worship them or serve them; for I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God..." (Exodus 20: 3-5).

Correct me if I am wrong, but God seems to rule out everything as idol material, as gods to be worshipped and served. He wants us to worship Him alone--the wily, inscrutable, all-powerful, all-loving God of the Universe.

And how do we know if we worship the real God? I like Tim Keller's advice:

Only if your God can say things that outrage you and make you struggle will you know that you have gotten hold of a real God and not a figment of your imagination.

—Wayne S.

(Tim Keller quote from The Reason for God

Thursday, December 17, 2009

C. S. Lewis on Christ as Myth

You ask me my religious views: you know, I think, that I believe in no religion. There is no proof for any of them, and from a philosophical standpoint Christianity is not even the best. All religions, that is, all mythologies to give them their proper name, are merely man's own invention--Christ as much as Loki. Primitive man found himself surrounded by all sorts of terrible things he didn't understand--thunder, pestilence, snakes, etc: what more natural than to suppose that these were animated by evil spirits trying to torture him. These he kept off by cringing to them, singing songs and making sacrifices, etc. Gradually from being mere nature-spirits these supposed being(s) were elevated into more elaborate ideas, such as old gods; and when man became more refined he pretended that these spirits were good as well as powerful.

Thus religion, that is to say mythology, grew up. Often, too, great men were regarded as gods after their death--such as Heracles or Odin: thus after the death of a Hebrew philosopher Yeshua (whose name we have corrupted into Jesus) he became regarded as a god, a cult sprang up, which was afterwards connected with the ancient Hebrew Jahweh-worship, and so Christianity came into being--one mythology among many, but the one we happened to have been brought up in...

--C. S. Lewis, on October 12, 1916 age 17.

Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened: and one must be content to accept it in the same way, remembering that it is God's myth where the others are men's myths: i.e. the Pagan stories are God expressing himself through the minds of poets, using such images as He found there, while Christianity is God expressing Himself through what we call "real things". Therefore it is true, not in the sense of being a "description" of God (that no finite man could take in) but in the sense of being the way in which God chooses to (or can) appear to our faculties. The "doctrines" we get out of the true myth are of course less true: they are translations into our concepts and ideas of that wh[ich] God has already expressed in a language more adequate, namely the actual incarnation, crucifixion and resurrection. Does this amount to a belief in Christianity? At any rate I am now certain (a) That this Christian story is to be approached, in a sense, as I approach the other myths. (b) That it is the most important and full of meaning. I am also nearly almost certain that it happened...

--C. S. Lewis, on October 18, 1931, age 32, around the time of his conversion to Christianity.

Both quotes are from Letters of C. S. Lewis

edited by Walter Hooper and W. H. Lewis

edited by Walter Hooper and W. H. Lewis

Thus religion, that is to say mythology, grew up. Often, too, great men were regarded as gods after their death--such as Heracles or Odin: thus after the death of a Hebrew philosopher Yeshua (whose name we have corrupted into Jesus) he became regarded as a god, a cult sprang up, which was afterwards connected with the ancient Hebrew Jahweh-worship, and so Christianity came into being--one mythology among many, but the one we happened to have been brought up in...

--C. S. Lewis, on October 12, 1916 age 17.

Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened: and one must be content to accept it in the same way, remembering that it is God's myth where the others are men's myths: i.e. the Pagan stories are God expressing himself through the minds of poets, using such images as He found there, while Christianity is God expressing Himself through what we call "real things". Therefore it is true, not in the sense of being a "description" of God (that no finite man could take in) but in the sense of being the way in which God chooses to (or can) appear to our faculties. The "doctrines" we get out of the true myth are of course less true: they are translations into our concepts and ideas of that wh[ich] God has already expressed in a language more adequate, namely the actual incarnation, crucifixion and resurrection. Does this amount to a belief in Christianity? At any rate I am now certain (a) That this Christian story is to be approached, in a sense, as I approach the other myths. (b) That it is the most important and full of meaning. I am also nearly almost certain that it happened...

--C. S. Lewis, on October 18, 1931, age 32, around the time of his conversion to Christianity.

Both quotes are from Letters of C. S. Lewis

Tuesday, December 8, 2009

God in the equation

I am a person who has problems believing, and yet, in spite of them, perhaps because of them, I do believe. I think the right to doubt is one of the most important rights given to human beings. But I believe in God. In fact I never stopped believing in God—that's why I had the problem, the crisis of faith. If I had stopped believing, then I would have been much more at peace. It would've been okay to be disappointed in human beings. what else could you expect from a human being who is the object of seduction and all kinds of ambition, right? It is easier if God doesn't enter the equation. The moment you start to believe in God, then how can you accept the world? Do you then accept God's absence? Do you accept God's silence? God—why doesn't he tried to make people better, make them lead better lives and be kinder to each other? Why doesn't he do it? A few times he gave up. But the floods were not a punishment for sins against God but for crimes against each other. what are they doing to themselves? God thought. So he brought the floods. And it didn't help. I cannot understand two aspects of human nature: indifference and nastiness. I cannot understand. At my age, I should be able to understand. But I cannot. I do not understand. Indifference and nastiness on every level, on petty levels and on high levels.

—Elie Wiesel, Author, Holocaust Survivor, Nobel Peace Prize Winner, quoted in The God Factor, by Cathleen Falsani.

—Elie Wiesel, Author, Holocaust Survivor, Nobel Peace Prize Winner, quoted in The God Factor, by Cathleen Falsani.

Sunday, November 15, 2009

Love like God, or love of God?

Perhaps the most quoted New Testament writer of all is not Paul, but the Apostle John. There are two reasons for this: John 3:16 and First John 4:8.

Unfortunately, many (mostly those outside the faith) want to make the second verse mean something it does not. They want it to mean that "If we love, we know God." But it doesn't. If we love, we are perhaps most like God, but we do not neccessarily know Him. I may sit down and play "Yesterday" on the guitar, but I do not know Paul McCartney.

John speaks about love a lot. Severty-nine times it is used in his writings. It is obvious that he thinks love is a paramount virtue, and evidence of a true spiritual faith. One would think the writer John would be a perfect text for those who say "the essence of spirituality is love."

But John also says something else. In the same letter in which he wrote "God is love," he writes this:

Many Americans, Christian or not, simply choose to ignore the Jesus stuff. A Pew Research Center survey in 2007 found that in all major religions (including evangelical Christianity), a majority felt there were many roads to eternal life. Even our president unashamedly supports this view. But John doesn't. And neither does the rest of the Bible.

John sums it up this way:

—W. S.

*John uses the term antichrist here in a generic sense, as someone who is anti-Christ, not as some prophetic future ruler.

Illustration: Helping Hands by Nadeem Chughtai

"For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish, but have eternal life." John 3:16

"The one who does not love does not know God, for God is love." 1 John 4:8The former verse is, of course, a great promise to believers and unbelievers alike. The latter is a promise, too, that we will know the true spiritual state of our hearts by our actions towards others.

Unfortunately, many (mostly those outside the faith) want to make the second verse mean something it does not. They want it to mean that "If we love, we know God." But it doesn't. If we love, we are perhaps most like God, but we do not neccessarily know Him. I may sit down and play "Yesterday" on the guitar, but I do not know Paul McCartney.

John speaks about love a lot. Severty-nine times it is used in his writings. It is obvious that he thinks love is a paramount virtue, and evidence of a true spiritual faith. One would think the writer John would be a perfect text for those who say "the essence of spirituality is love."

But John also says something else. In the same letter in which he wrote "God is love," he writes this:

"By this you know the Spirit of God: every spirit that confesses that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God; and every spirit that does not confess Jesus is not from God; this is the spirit of the antichrist*, of which you have heard that it is coming, and now is already in the world." 1 John 4: 2-3Yikes! Suddenly we find that loving one another is not enough. We actually need to confess that Jesus is God, sent from God. Here's where the "God is love" crowd drops back. But in doing so, don't they really negate the love part, too? I mean, if John is dead-set on this Jesus stuff, can we trust him on the love stuff?

Many Americans, Christian or not, simply choose to ignore the Jesus stuff. A Pew Research Center survey in 2007 found that in all major religions (including evangelical Christianity), a majority felt there were many roads to eternal life. Even our president unashamedly supports this view. But John doesn't. And neither does the rest of the Bible.

John sums it up this way:

Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God; and everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. The one who does not love does not know God, for God is love.Yes, God is love. And Jesus is the evidence. The only evidence.

By this the love of God was manifested in us, that God has sent His only begotten Son into the world so that we might live through Him. In this is love, not that we loved God, but that He loved us and sent His Son to be the propitiation for our sins.

Beloved, if God so loved us, we also ought to love one another.

No one has seen God at any time; if we love one another, God abides in us, and His love is perfected in us. By this we know that we abide in Him and He in us, because He has given us of His Spirit.

We have seen and testify that the Father has sent the Son to be the Savior of the world. Whoever confesses that Jesus is the Son of God, God abides in him, and he in God.

We have come to know and have believed the love which God has for us. God is love, and the one who abides in love abides in God, and God abides in him.

By this, love is perfected with us, so that we may have confidence in the day of judgment; because as He is, so also are we in this world.

There is no fear in love; but perfect love casts out fear, because fear involves punishment, and the one who fears is not perfected in love.

We love, because He first loved us. (1 John 4:7-19)

—W. S.

*John uses the term antichrist here in a generic sense, as someone who is anti-Christ, not as some prophetic future ruler.

Illustration: Helping Hands by Nadeem Chughtai

Saturday, October 31, 2009

Hide and Seek

Over time, I have learned two things about my religious quest: First of all, that it is God who is seeking me, and who has myriad ways of finding me. Second, that my most substantial changes, in terms of religious conversion come through other people. Even when I become convinced that God is absent from my life, others have a way of suddenly revealing God's presence.

—Kathleen Norris, in Amazing Grace, a Vocabulary of Faith

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Christopher Hitchens on Sincere Faith

Christopher Hitchens is a renowned author, journalist and atheist apologist. He is currently featured in the documentary Collision, a record of a series of cross-country debates with Pastor Douglas Wilson, senior fellow at New St. Andrews College. Just as all evangelicals are not nosy hypocrites, not all atheists are grouchy critics. In an article in Slate, it will be surprising to some what Hitchens finds praiseworthy of his debate partner:

"Wilson isn't one of those evasive Christians who mumble apologetically about how some of the Bible stories are really just 'metaphors.' He is willing to maintain very staunchly that Jesus of Nazareth was the Christ and that his sacrifice redeems our state of sin, which in turn is the outcome of our rebellion against God. He doesn't waffle when asked why God allows so much evil and suffering—of course he 'allows' it since it is the inescapable state of rebellious sinners. I much prefer this sincerity to the vague and Python-esque witterings of the interfaith and ecumenical groups who barely respect their own traditions and who look upon faith as just another word for community organizing."

Monday, October 12, 2009

O. Hallesby: Prayer

I need not exert myself and try to force myself to believe, or try to chase doubt out of my heart. Both are equally useless. It begins to dawn on me that I can bring everything to Jesus, no matter how difficult it is; and I need not be frightened away by my doubts or my weak faith, but only tell Jesus how weak my faith is. I have let Jesus into my heart. And He will fulfill my heart’s desire. —O. Hallesby in Prayer.

Friday, October 9, 2009

Witness

A man is not primarily a witness against something. That is only incidental to the fact that he is a witness for something. A witness, in the sense that I am using the word, is a man whose life and faith are so completely one that when the challenge comes to step out and testify for his faith, he does so, disregarding all risks, accepting all consequences.

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

The Agnostic

I can well imagine an athiest's last words: "White, white! L-L-Love! My God!"—and the deathbed leap of faith. Whereas the agnostic, if he stays true to his reasonable self, if he stays beholden to dry, yeastless factuality, might try to explain the warm light bathing him by saying, "Possibly a f-f-failing oxygenation of the b-b-brain," and, to the very end, lack imagination and miss the better story. — Yann Martel, Life of Pi.

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

The faith of last resort

There is no inherent superiority in being a Christian. C. S. Lewis was once asked, “Which religion is the best?” He replied, “While it lasts, the religion of worshiping oneself is the best.” The point I think Lewis was making was this: Christianity is the faith of last resort. It is one you choose when all the others have proved inadequate. It is the one you choose when you have run out of choices that allow you to run the show.

And the reason it is the last choice is simple—it expects all of us. Properly devoted to, it requires us to die.

-- W. S.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)