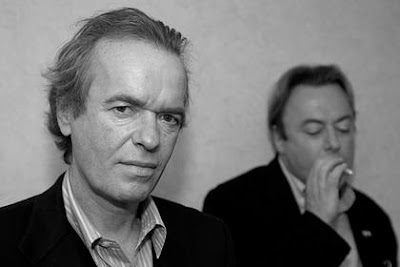

As many of you know, commentator, essayist and noted atheist

Christopher Hitchens is battling a vigorous case of esophageal cancer. He recently wrote in

Vanity Fair about all the Christians (and those of other faiths) who are praying for him. It is a must-read article. Hitchens asks some very interesting questions: To those who say the cancer is his punishment for speaking out against faith, he notes, "Almost all men get cancer of the prostate if they live long enough: it’s an undignified thing but quite evenly distributed among saints and sinners, believers and unbelievers. If you maintain that god awards the appropriate cancers, you must also account for the numbers of infants who contract leukemia."

One of the most interesting things he says is to those who are praying for his salvation. He thanks them, but tells them don't expect a last minute grasp at eternity:

"Suppose I ditch the principles I have held for a lifetime, in the hope of gaining favor at the last minute? I hope and trust that no serious person would be at all impressed by such a hucksterish choice."

Impressed? No. But we are convinced it is possible, if unlikely.

Many people, smart people like Mr. Hitchens, believe that God somehow operates with the same sense of fairness in which we operate. Therefore, they conclude that it somehow just isn't possible (or fair) that person A can live his life obediently, perhaps painfully, seeking to follow and please God, while person B, in the words of some clever wit, goes to the grave "skidding in sideways, Chardonnay in one hand, chocolate in the other," and expects the same consideration, and indeed the same destination, just because at the last minute they believed.

But God doesn't use that metric. In some sort of divine calculus that really doesn't seem to add up to us, God is less concerned with when we believe, but that we believe. How else could you explain the thief on the cross being promised Paradise?

William Camden, an English historian in Shakespeare's day, wrote in Remains (1623) of a dissolute man who died when he fell from his horse:

My friend, judge not me,

Thou seest I judge not thee;

Betwixt the stirrop and the ground,

Mercy I askt, mercy I found.

Perhaps Mr. Hitchens thinks that is a bridge too far. I will still pray for him. And I easily believe, in his case, that one day he may enter eternity with God, "skidding in sideways, Johnny Walker Black in one hand, a Rothmans cigarette in the other... ."

He says if word ever gets out that, in some sort of delirium, he calls upon God to save him, we should not believe a word of it. How curious that, of all he has said that he wants us to believe, that would be suspect.

God be with you, Christopher Hitchens.

—Wayne S.